| Katya Sander | e@katyasander.net |

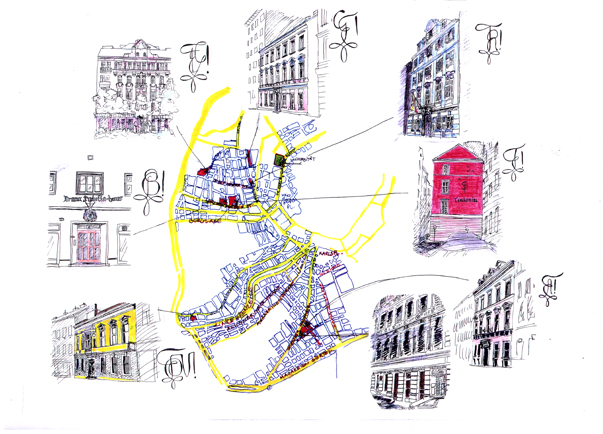

| Mapping Vienna In Do It Yourself - Mapping and Instructions, curated by Simon Sheikh, Bricks and Kicks, Vienna, 1997 (catalogue).  For ‘Mapping Vienna’ I created a tourist map of Vienna, photocopied it and placed it around Vienna in railway stations, tourist information centers, cafes, bars, libraries, and other places where visitors would normally pick up information and maps. However, rather than making the city more accessible, my map marked sites that were definitely not accessible to visitors, travelers, strangers or ‘outsiders’. These were sites of exclusion rather than inclusion. At a quick glance the map might have looked like an ordinary tourist guide. Upon further inspection, however, it became obvious that it was ‘homemade’, drawn and colored in by hand. It also became clear that the map served a very narrow and subjective interest. The only sites marked on the map were buildings owned by the “Burschenshaften.” My map did not explain these sites, it only marked them. A visitor using the map would need to ask locals for an explanation. Most people living in Vienna know what the marked sites, the “Burschenschaften,” represent – though they rarely discuss them with foreigners. I located the buildings by walking around the city and by asking people I knew. The map was symbolic and "to be continued." People I met were surprised by the number of “Burschenschaften” buildings I had found. They are very discrete, like the power they incarnate – a power rooted in structures around access to, and production of, knowledge. Though almost invisible, these sites are nevertheless essential to Austrian politics and finance as they operate today.

“Burschenschaften” is difficult to translate – it is similar to the idea of “fraternity” or "brotherhood" in the US. The tradition of the "Burschenschaften" (or "brotherhoods") began with the first German universities, in Prague, Heidelberg and Vienna in the 14th century. "Burschenschaften" were student organizations where an older student (or “mensur”) would help an incoming student (or “fox”) with his studies. In return the "fox" had to serve the “mensur” and endure his humiliations. After a number of years, the fox could apply to become a “mensur” himself. For hundreds of years it was impossible to study at a university without joining a brotherhood. In 1815, the brotherhoods at German-speaking universities voted to officially continue observance of their traditional rules for membership: women, non-German men, and men who had not served in the army were all ineligible for membership. In later years, the anti-democratic and elitist Burschenschaften supported the Nazi Party, and was consequently banned following WWII. But by 1953 they began organizing again, especially at Austrian universities with traditionally strong faculties in medicine and law. In 1961, the Burschenschaften was officially reconstituted--with its old rules intact. By the Fall of 1996, the Burschenschaften counted more than 21,000 students and no less than 19,000 "Alte Herren" ("Old Gentlemen") who help the young graduates with their careers in return for loyalty. Secrecy around initiation rituals, loyalty towards brothers, as well as ideas of "German-ness" are still some of the binding factors in the Burschenschaften, not to mention the real estate. Investments in buildings ensure meeting space as well as cheap accommodation for student members. In Austria the Burschenschaften are known to be very strong and in fact running much of the Austrian political and financial sectors.

|